GAP — The Brand That Built America’s Closet (Then Forgot Why)

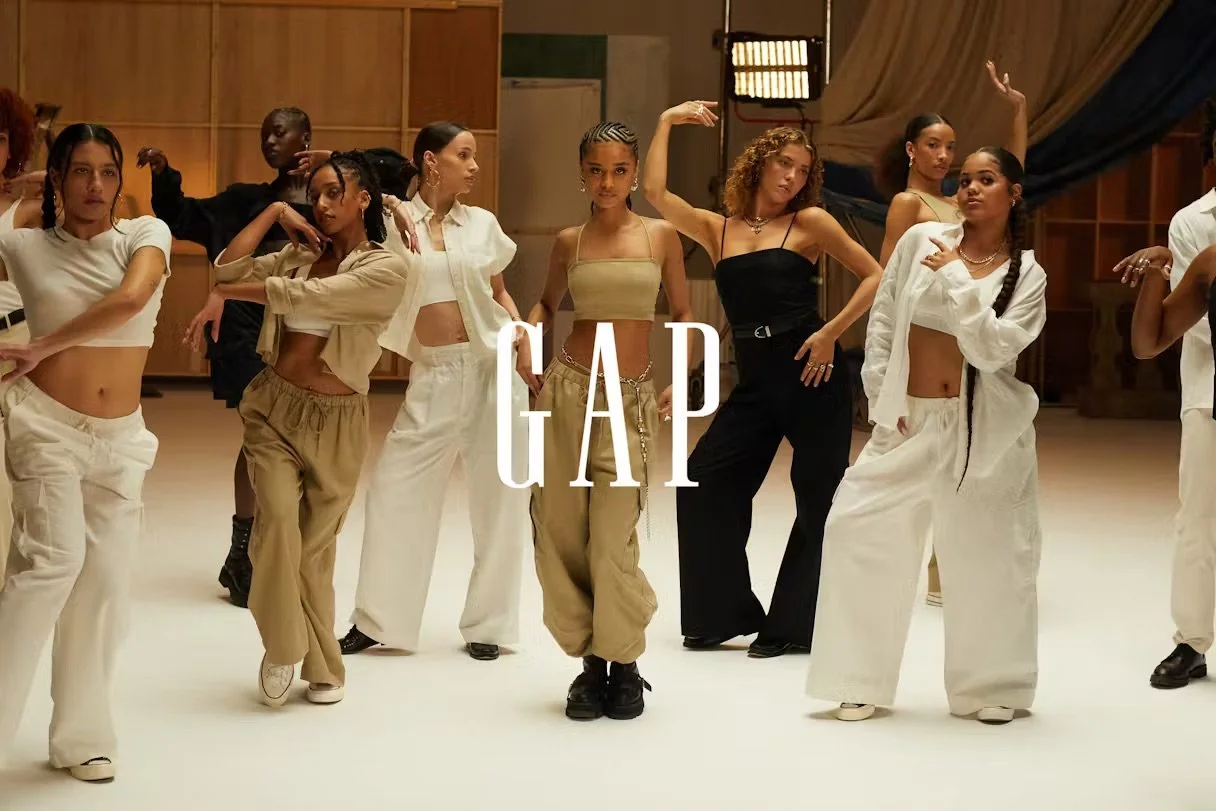

Image courtesy of GAP

There’s something haunting about watching a brand lose its identity in real time.

At its peak, Gap wasn’t just popular—it was everywhere. Everyone wore it. Everyone trusted it. It was the blueprint for American casual. But somewhere along the line, the brand that made “normal” look iconic got tangled in its own success. It scaled too fast. Stopped listening. Played it safe until no one was paying attention.

Today, Gap is still here—but it’s a little quieter. Fewer stores. Less noise. A new CEO with Barbie-era buzz. And a question hanging in the air:

Can a brand built on basics still matter when basics became... everyone’s baseline?

Act I: The Original Strategy Wasn’t Fashion—It Was Inventory

Gap didn’t start with a vision. It started with a problem. In 1969, Don Fisher couldn’t find a pair of Levi’s in his size. So he created the solution: a retail space that always had jeans, in every size, on every shelf.

That’s it. No brand story. No aesthetic. Just stock and reliability.

The original Gap store sold Levi’s jeans and vinyl records. It was youth culture in a clean package—an early version of curated Americana. But the real power move came a few years in: Gap cut Levi’s out entirely and started producing its own denim.

That changed everything.

By shifting to private label, Gap controlled margins, design, and supply chain. It became one of the first vertically integrated fashion retailers in the U.S., long before DTC startups turned that into a marketing line.

The clothes? Clean. Accessible. Slightly suburban. But that was the point. Gap made “normal” feel like a choice.

By the early 1980s, Gap had over 200 stores and a growing grip on American retail. It wasn’t loud. It wasn’t trendy. It just worked.

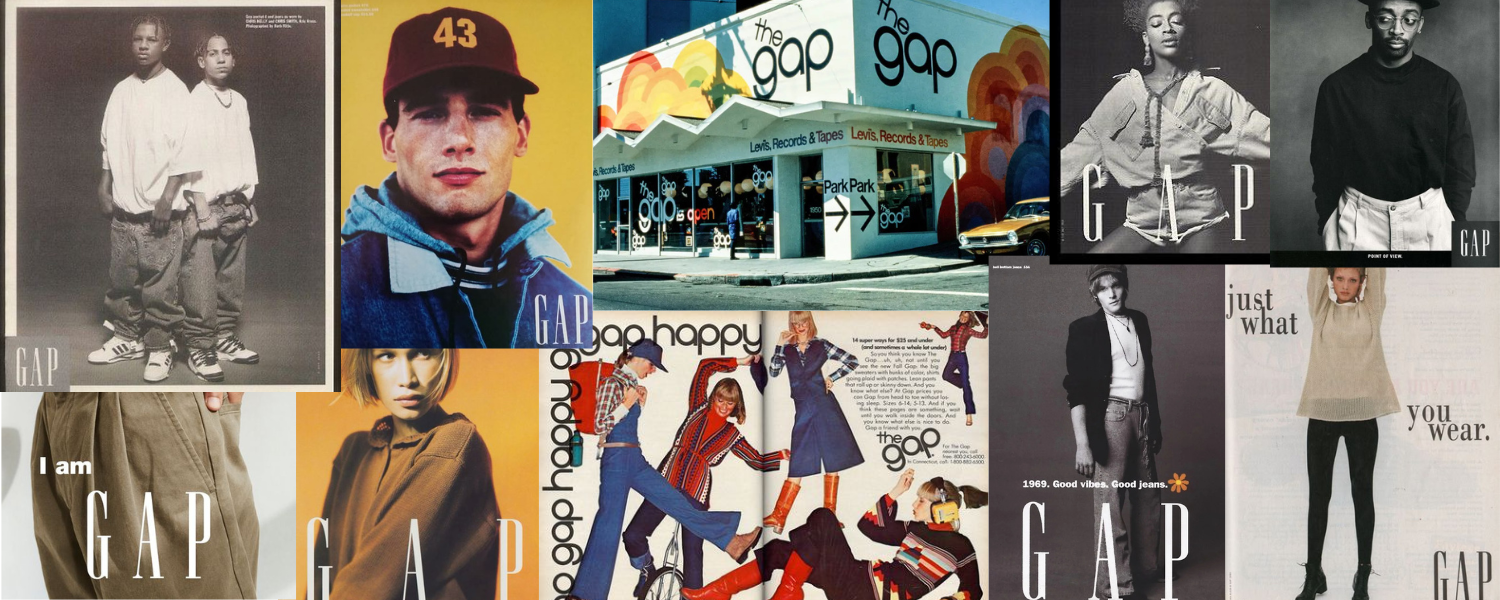

All images courtesy of GAP, Pinterest

Act II: The Drexler Era — When Gap Defined Cool by Doing Less

If Don Fisher built the machine, Mickey Drexler made it matter.

He stepped in during the early ‘80s and completely re-coded Gap’s cultural relevance. Drexler didn’t just scale the brand—he gave it taste. He stripped it back, focused on clean lines, solid colors, and made the brand feel editorialwithout being high fashion.

White tees, navy hoodies, straight-leg denim. Uniform dressing before it was a trend.

Gap’s marketing was legendary. Black-and-white portraits. Iconic ad campaigns. Shot by Herb Ritts and Annie Leibovitz. Featuring Spike Lee, Madonna, Lenny Kravitz. All shot like fine art—not product promos. Gap wasn’t shouting. It was positioned.

And it worked.

In the ‘90s, Gap was untouchable. The entire country was in khakis. Mall stores were packed. Athletes, actors, politicians—everyone wore it. The brand became a default. A vibe. A trust signal.

And Drexler didn’t stop there.

He expanded the empire with Banana Republic (acquired and rebranded into luxury-lite), Gap Kids, BabyGap, and in 1994, the killer app: Old Navy.

Old Navy was a low-price juggernaut built to crush discount chains like Walmart and Kmart—but it had just enough style to feel current. And it exploded.

By the late ‘90s, Gap Inc. was pulling in over $14 billion annually. It wasn’t just a company. It was the uniform of the Western world.

Act III: Scaling Killed the Signal

The collapse didn’t come with a bang—it was a slow drift.

By the early 2000s, Gap had overexpanded. There were too many stores in the same malls. The collections started to feel repetitive. The brand lost the ability to surprise people. Basics became boring, and competitors started catching up.

Fashion was shifting—fast.

Fast fashion surged. H&M and Zara offered cheap, fast, styled-up options. DTC brands like Everlane and later Uniqlo started delivering better fits, better values, and stronger brand missions. Gap didn’t pivot. It doubled down on the same formula that made it great in the ‘90s.

Meanwhile, Old Navy overtook Gap as the revenue driver. Banana Republic drifted into irrelevance. Creative leadership changed constantly, but no one stuck long enough to course-correct.

In 2002, Drexler was out. Fired.

From there, Gap Inc. spent two decades trying to figure out what it was supposed to be.

Act IV: The Identity Crisis That Wouldn’t End

Gap tried everything:

A failed logo rebrand in 2010 that lasted six days- LoL

Random collabs with Kanye West and Sarah Jessica Parker.

A short-lived men's athleisure brand (Hill City—RIP).

A near spin-off of Old Navy that got cancelled last-minute in 2020.

Meanwhile, the flagship brand just kept... existing.

Not awful. Not amazing. Just sitting in malls that fewer and fewer people wanted to shop in.

By 2020, the situation was clear:

Gap had no real point of view.

The product wasn’t bad—but no one felt anything about it.

Stores were closing. Sales were flat. Brand perception was background noise.

Even as it tried to modernize, Gap felt like it was always catching up—never leading, never reshaping the conversation like it did in the '90s.

Act V: The Attempted Reset — Richard Dickson Enters the Chat

In 2023, Gap Inc. brought in a new CEO: Richard Dickson, the man who turned Barbie into a cultural event again. Literally.

Dickson isn’t a fashion guy. He’s a brand revivalist. His entire playbook is about unlocking nostalgia, telling better stories, and making old brands feel iconic again.

And that’s exactly what Gap needs.

So far, his moves have been cautious but intentional:

Closing hundreds of underperforming stores.

Reinvesting in e-commerce and digital UX.

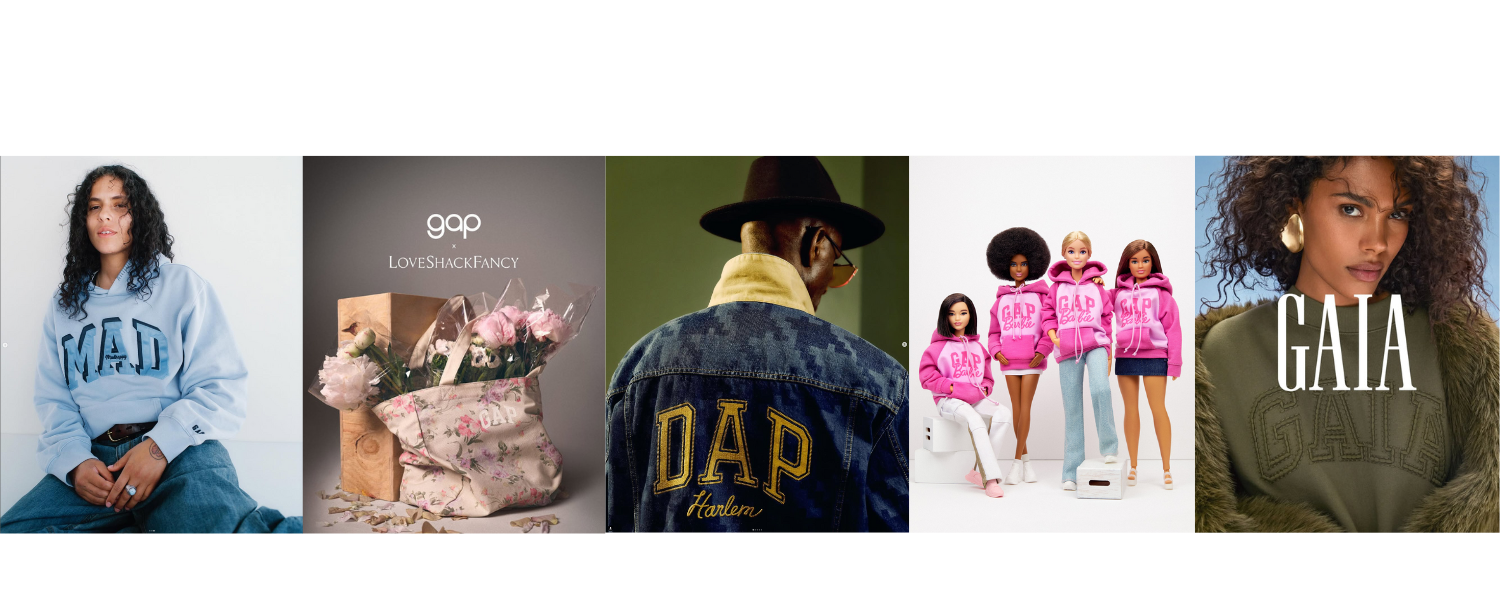

Focusing on cultural storytelling, especially through collabs like Gap x Dapper Dan and Gap x LoveShackFancy.

Reframing the brand around elevated basics, clean design, and 90s-coded minimalism—which, conveniently, is trending again.

The company is still split between four main brands:

Gap (core basics + nostalgia)

Old Navy (value engine)

Banana Republic (being repositioned upmarket again)

Athleta (wellness-focused and still promising, but inconsistent)

The financials are steady—but not thrilling:

Revenue is hovering around $15–16B, but margins are tight.

Gap brand itself remains the weakest performer of the four.

Old Navy still does volume, but its brand heat is fading.

Banana Republic is in a constant identity reboot.

Athleta has growth potential, but isn't dominating the way Lululemon is.

So... Is There a Future for Gap?

That depends on whether they can do three things:

Rediscover a Point of View

If Gap is just basics, it loses. If it’s basics with taste, history, and purpose—it has a shot.

The culture is already flirting with 90s revival. Gap could ride that wave if it moves with intention.Let Go of Scale as the Goal

Fewer stores. Better storytelling. Smaller drops. Controlled collabs. Gap can’t win by being everywhere—it has to win by being right somewhere.Treat the Brand Like IP, Not Inventory

This is where Dickson might shine. If Barbie taught us anything, it’s that the story matters more than the SKU. Gap doesn’t need to launch a million products. It needs to mean something again.

Closing Thought

Gap’s biggest mistake wasn’t falling behind on trends. It was forgetting why people cared in the first place.

It didn’t win the ‘90s because it was everywhere. It won because it was clear, confident, and consistent. The product wasn’t just basic—it was intentional. It made everyday style feel like a choice.

If Gap can find that clarity again—and pair it with a slower, sharper strategy—it doesn’t need a comeback. It needs a reset.

And in a chaotic retail world full of noise, clarity might be the most underrated flex of all.