The Rise, Fall, and Quiet Rebirth of J.Crew

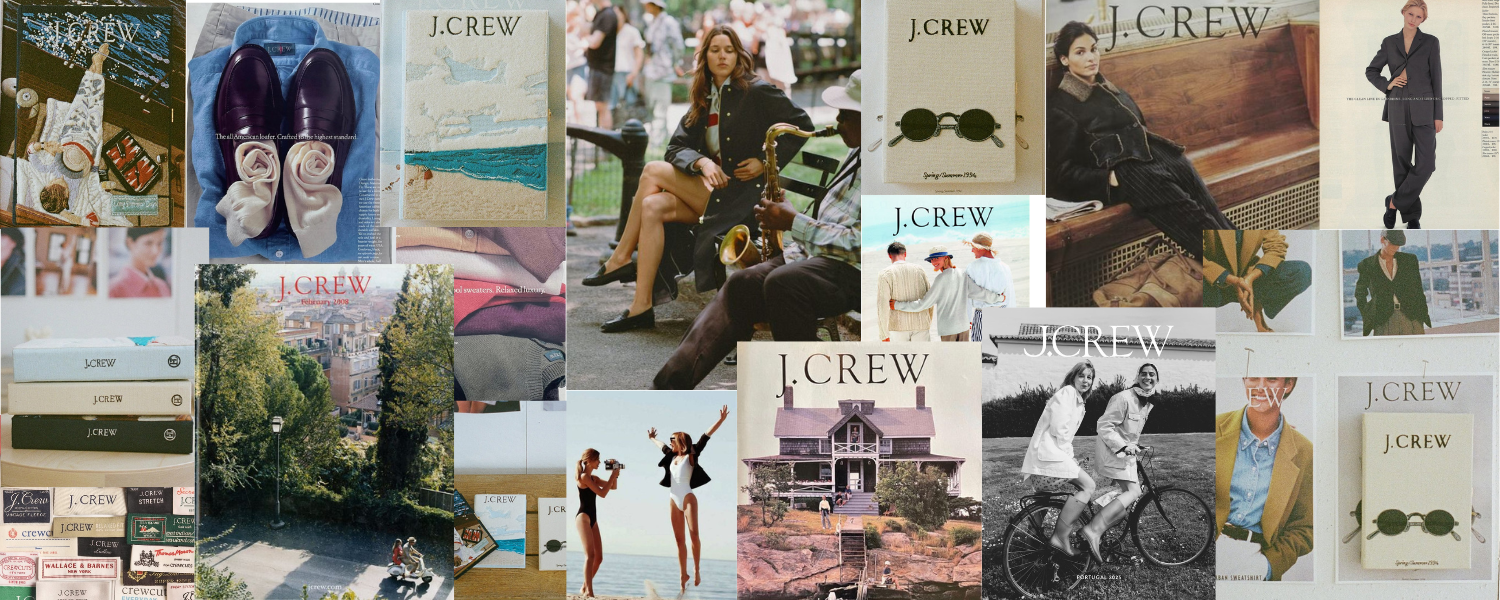

Images courtesy of J. Crew

How the Preppiest Brand in America Blew It

From Michelle Obama to mall-brand meme—J.Crew lived fast, dressed well, and crashed hard.

There was a time when J.Crew defined cool. Not flashy, not designer, just clean, polished, editorial-level prep. The kind of brand that made you feel like you had your life together—even if all you really had was a chambray shirt and a pair of broken-in chinos.

But somewhere between the sequin skirts and the IPO dreams, the brand lost the plot. It stopped evolving. It got expensive without getting better. Then came the bankruptcy filing.

Now? J.Crew’s rebuilding. Quietly. Strategically. No hype drops, no billboards—just better fits, smarter hires, and a return to what made it great in the first place. This isn’t a comeback story. It’s a case study.

Act I — The Blueprint: Catalog Cool & Coastal Prep

Before Instagram, before Shopify, before “DTC” was even a term—there was J.Crew. Founded in 1983 by Arthur Cinader and his daughter Emily Woods, it was built on the old-school power of catalogs. Think L.L.Bean, but sleeker. Ivy League energy with an art director’s eye.

The catalog strategy was brilliant for its time. It gave J.Crew total control over how the product showed up: styled, aspirational, and always just a little out of reach. You weren’t just buying a navy blazer. You were buying into a lifestyle. Sailing, summers in Cape Cod, long weekends at brownstone dinner parties—American prep without the generational wealth requirement.

Retail started slow. A few stores here and there—mostly upscale malls and select city corners. The product was clean. Reliable. Slightly elevated basics for people who wanted to look sharp without doing too much. And it worked.

No fast fashion. No hype. Just tasteful color palettes, good lighting, and that sweet spot between Banana Republic and Ralph Lauren. The kind of brand you trusted to get it right.

Act II — The Golden Era: Drexler, Jenna, and the Editorial Takeover

Everything changed in 2003.

That’s when Mickey Drexler, the guy who built Gap into a cultural force in the ‘90s, took the helm. And right alongside him? Jenna Lyons—a behind-the-scenes designer who would become the face (and brain) of the brand’s entire aesthetic shift.

This is when J.Crew stopped selling clothes and started selling a mood.

The styling flipped. Sequins with denim. Leopard print with loafers. Sweatshirts layered under blazers. Lyons turned the catalog into an editorial, and the website into a lookbook. Suddenly, J.Crew wasn’t just a reliable basics brand—it was a style authority.

Retail followed. Stores got a facelift. J.Crew opened concept shops and city flagships that felt more boutique than mall. The Liquor Store in Tribeca became a cultural moment—an old bar turned men’s-only shop with curated records and whiskey on the shelf.

And then came the Michelle Obama era.

When the First Lady wore J.Crew on The Tonight Show—and again for the 2009 Inauguration—the brand hit peak relevance. Vogue approved. Celebrities styled it high-low. Editors were obsessed. It was accessible, but aspirational. Preppy, but playful. J.Crew was the blueprint for American fashion retail.

Even Madewell, their secondary label launched in 2006, started pulling its weight—growing a cult following and eventually outpacing the parent brand in relevance.

For a few years, it felt like J.Crew could do no wrong.

Act III — The Strategic Collapse: Ego, Overreach, and Missed Signals

The downfall didn’t happen overnight—but the red flags were there.

After years of riding high on cultural cachet and creative heat, J.Crew started making moves that looked ambitious on the surface… but shaky underneath. The problem? They confused taste with scale.

First came the 2011 private equity buyout—a $3 billion leveraged deal led by TPG Capital and Leonard Green & Partners. It loaded J.Crew with $1.7 billion in debt. That debt became the noose. It meant pressure to grow fast, open more stores, increase margins, hit aggressive KPIs—all while fashion was shifting under their feet.

Instead of doubling down on brand clarity, they tried to be everything.

They launched J.Crew Mercantile, a budget version aimed at competing with fast fashion. But it confused customers. Was this the elevated brand Michelle Obama wore? Or the cheaper one in the strip mall next to Old Navy?

They expanded too hard into factory outlets and mall real estate, even as foot traffic dropped across the U.S. retail sector. While DTC startups like Everlane and Warby Parker were building modern, agile e-comm ecosystems, J.Crew was still acting like it was 2010—with a clunky website and outdated email marketing strategy.

Worse? The creative direction froze. Jenna Lyons’ aesthetic that once felt fresh started to feel predictable. The chambray shirt, the sequins, the high-low styling—it didn’t evolve. And by the time she left in 2017, the brand was directionless.

Meanwhile, Gen Z was entering the chat. Streetwear, normcore, and hyper-individualized style were taking over. J.Crew wasn’t part of that conversation. It was stuck in its own bubble—overpriced, under-innovated, and out of sync.

Behind the scenes, the leadership churned, the product suffered, and customers noticed. Quality slipped, sizing got inconsistent, prices kept climbing. People weren’t just disappointed—they were vocal about it. Twitter threads, Reddit rants, fashion forum takedowns. J.Crew had become the brand you used to love.

And then… the pandemic hit.

Act IV — The Fall: Bankruptcy and the Bottoming Out

By 2020, J.Crew was already in survival mode—too many stores, too much debt, and no cultural heat to carry it through.

Then came COVID.

As lockdowns hit and retail came to a standstill, J.Crew became the first major U.S. retailer to file for bankruptcyduring the pandemic. On May 4, 2020, they entered Chapter 11 with more than $1.65 billion in debt and no liquidity runway.

This wasn’t a shock. It was a slow bleed that finally got too deep to ignore.

Store closures followed. Around 67 locations were shut down, including underperforming mall stores and some J.Crew Factory outlets. The goal was survival—not reinvention.

The bankruptcy wiped out its private equity structure. TPG and Leonard Green were out. A new ownership group led by Anchorage Capital took over, giving J.Crew a lifeline—but not a reboot.

This wasn’t the kind of collapse that got a flashy Netflix doc or a social media post-mortem. No public meltdown, no massive scandal. Just quiet, corporate exhaustion. A brand that had been stretched, stripped, and milked for years… finally tapped out.

At this point, J.Crew wasn’t even part of the fashion conversation anymore. It was a ghost of what it once was—a brand people used to wear when they cared about dressing well, but not too loud.

The question now wasn’t whether they could be cool again.

It was whether they could even survive.

Act V — The Quiet Comeback: Brendon, Libby, and Soft Power Plays

After the dust settled from bankruptcy, J.Crew didn’t announce a big rebrand or try to ride some viral trend. Instead, they started rebuilding the old-fashioned way—by getting their product, leadership, and positioning right.

First, Libby Wadle was promoted to CEO in late 2020. She’d been with the company for years and understood the DNA of both J.Crew and Madewell. But more importantly—she wasn’t trying to be a star. No ego, no press tour. Just clean strategy and stability.

Then came the big creative play: in 2021, J.Crew hired Brendon Babenzien (co-founder of Noah, ex-creative director at Supreme) to lead menswear.

That was the signal.

Babenzien didn’t come from a traditional prep background. He came from downtown streetwear, skate culture, and cult-level brand building. He brought credibility, edge, and a fresh perspective—without ditching the core of what J.Crew was. His version of the brand was less “Hamptons brunch,” more “off-duty architect in Montauk.”

You could feel the shift immediately.

The menswear line started hitting again—better cuts, real fabrics, and styling that felt lived-in. Less catalog, more character. The kind of stuff that looked good without trying too hard.

But the bigger move? They stopped chasing volume.

J.Crew began trimming the fat. Store count came down. The focus moved to flagship-quality experiences, better merchandising, and smarter e-comm. They didn’t need to be everywhere—they just needed to be right in the places that mattered.

They leaned into limited drops and smaller batch runs. Instead of overwhelming customers with 200 SKUs a season, they started curating. Reintroducing classics with intention. Reframing heritage as a flex, not a crutch.

Social media got quieter but smarter. The tone shifted. No more forced trend-chasing. Just solid photography, personal storytelling, and soft-spoken confidence.

Collabs started landing again—New Balance, Wallace & Barnes, Noah-adjacent aesthetics. The kind of drops that don’t scream, but still sell out.

They’re not trying to win Gen Z’s For You Page. They’re trying to earn back the trust of people who actually care about how things fit, feel, and last.

It’s working—slowly.

This isn’t a brand revival. It’s a recalibration.

Images courtesy of J. Crew

Strategy & Financial Breakdown: What’s the Play Now?

J.Crew isn’t back in a big, public way—but behind the scenes, the rebuild is methodical. This is no longer a bloated retail giant trying to scale its way out of irrelevance. It’s a leaner, more focused brand trying to win back margin, credibility, and long-term loyalty.

Retail Footprint: Less Mall, More Meaning

Post-bankruptcy, they shut down dozens of underperforming stores.

The goal isn’t saturation anymore. It’s precision.

Flagship and lifestyle-center locations are prioritized. Think fewer stores, better stores.

Mall presence still exists, but the brand’s not depending on foot traffic to drive growth like it used to.

They’re rebuilding the retail channel like a DTC brand would—measured, experiential, and supported by e-commerce instead of trying to compete with it.

E-Commerce & Digital Moves

The website has gotten cleaner, more curated, and less chaotic.

Email marketing and product storytelling are sharper—no more cluttered sales spam.

Still behind the best DTC players, but they’re catching up with:

Smarter product pages

Style guides and editorials

Better mobile UX

The site finally feels like it belongs in 2024.

The shift is subtle but strategic: less about flashy rebrands, more about UX that makes the clothes feel special again.

Product & Pricing: Value Recalibrated

Prices haven’t dropped, but the quality has come back up—and customers are noticing.

They’re putting money into fabric, fit, and construction, especially in menswear.

Less SKU bloat = cleaner inventory = less discounting = better margins.

Babenzien’s menswear has that Noah-style approach: drop a few perfect pieces, make them count.

They're trying to rebuild pricing power the hard way—by earning it.

What We Know Financially (Post-Bankruptcy)

J.Crew Group is now private (under Anchorage Capital), so there are no public quarterly earnings.

But based on industry reporting and store activity:

Store closures and restructuring cut major overhead.

Madewell continues to outperform J.Crew in revenue, but J.Crew is regaining brand equity.

Gross margins are likely recovering due to less discounting and better assortment control.

They’re no longer trying to IPO Madewell—suggesting a tighter long-term play rather than a short-term flip.

The bankruptcy wiped the slate clean—and that gave them space to breathe. Now they can actually invest in product, creative, and tech again without servicing massive interest payments.

The Strategic Shift in One Line:

They stopped trying to be big and started trying to be right.

What J.Crew Teaches Us

J.Crew isn’t just a fashion brand. It’s a case study in what happens when style, strategy, and scale stop speaking the same language.

At its peak, it was untouchable. A masterclass in editorial retail. The kind of brand that made middle America feel like they were in on something exclusive. But it fell into the same trap so many brands do—it confused momentum for invincibility.

Here’s the playbook:

You can’t scale identity. Brand equity doesn’t compound just because your store count does.

You have to evolve. A signature look becomes a uniform fast—and customers get tired.

Technology matters. You can’t be a modern retailer with a catalog-era mindset.

Private equity isn’t a growth strategy. It’s a time bomb if you don’t know what to do with the fuse.

Relevance can’t be bought. It’s earned—every season, every drop, every campaign.

What’s happening now isn’t flashy. It’s not loud. But it’s smart.

J.Crew’s not chasing hype. It’s rebuilding trust. One better fit, one smaller batch, one strategic hire at a time.

And in a landscape where most brands are burning through trends to stay alive, playing the long game, I believe is the boldest move of all.